When does a performance begin and when does it end? Does it only exist when it is staged in front of an audience, or does its life also exceed that transitory moment? Is the actual showing of the work performance’s primary mode of existence? Or could it be that the allure of the act tends to make us forget about the gamut of creative decisions, daily rehearsals, and preparatory materials that determine its appearance on stage and yet remain absent from it? How, when, and where exactly does a performance come into being?

The international conference Tracing Creation is aimed at exploring those processes that, strictly speaking, precede the moment a performance is staged but which nevertheless leave their mark on its form, structure, or content, thus playing a crucial role in what is presented to the public.

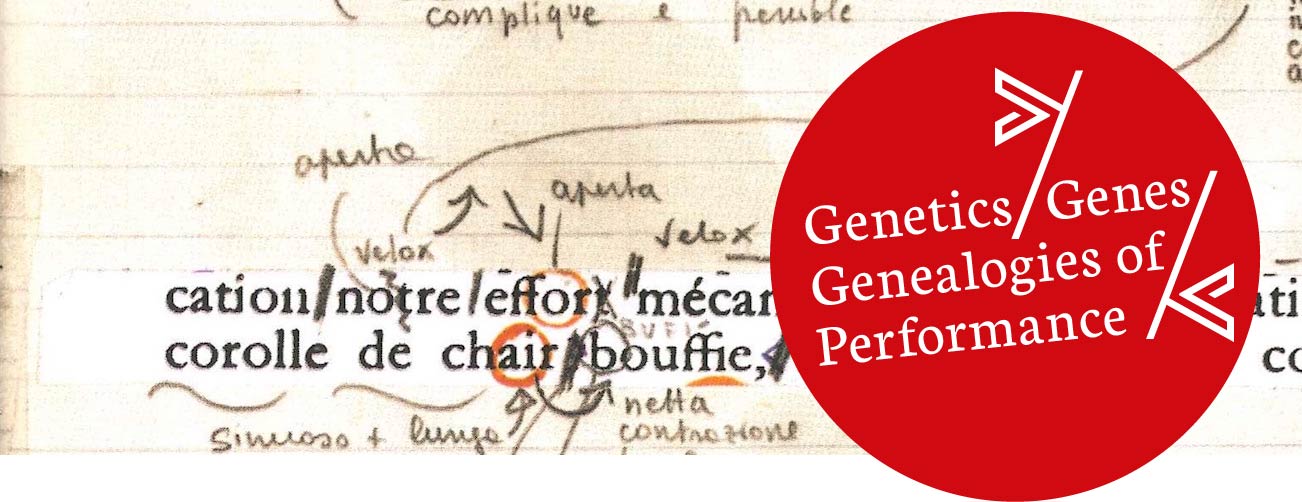

By proposing Genetics, Genes, and Genealogies as three anchor points around which investigations into the creative process may be clustered, the conference intends to stimulate the genetic study of performance as a newly emerging and promising branch of research in the field of theatre studies.

Genetics

Because the main focus of theatre studies has traditionally been the analysis of concrete stagings, the creative processes during which the work is made received only occasional attention. In contrast to the study of literature, which has a well-established tradition in genetic research, theatre scholars have only recently begun to inquire into the genetics of performance. Acknowledgement is growing that a thorough understanding of what happens on stage can greatly benefit from analysing those processes that take place beside it. However, as this is a relatively new research domain, there is a pressing need to develop solid methodologies that can enhance the genetic study of the performing arts.

Genes

In order to excavate the pre-histories of performance, the various documents generated in the course of artistic processes (including director’s notebooks, drawings, videos, audio recordings, et cetera) provide a rich yet underexplored source of information. In this respect, analysing performance from a genetic point of view immediately raises the vexed issue of how live performance relates to its material documentation: how can various means of notation, recording, and archiving adequately chart how a given work was created as well as enable its future restagings? In other words, how can different forms of documentation represent, preserve, and transmit what can be described as the genes of the performing arts.

Among these so-called genes, we could include the materials that are used to create performances, the aesthetic forms in which they take shape, and the dramaturgical strategies that undergird them. Rather than reinforcing the essentialist idea that live performance exists exclusively in and as embodied practice, the topic of genes intends to promote an expanded understanding of performance’s being by scrutinizing the various means and media that buttress its appearance.

Indeed, with the advent of what Hans-Thies Lehmann has famously called “postdramatic theatre” (1999), the modes of presentation and sources of inspiration employed by contemporary artists have become decidedly intermedial in nature, which calls for reflection on how changing media affect the genes of performance. The manifold intermedial transpositions that occur between page and stage, between screening and seeing, between noting and noticing are therefore of crucial importance to acquire a better insight into how the actual act leaves its traces and residues in a diversity of media that contribute to its creation and also secure its afterlife.

Genealogies

To call attention to the genetic study of the performing arts also calls for new perspectives on how their histories are written, told, or recorded. Scrutinizing how performance comes into being entails that grand narratives make place for seemingly trivial anecdotes, sketchy details, or small coincidences that perhaps occur in the margins, but which may bear unexpected importance on the creation of the work. Any increased interest in the genetics of performance is therefore likely to inspire a form of historiography that is close to Michel Foucault’s notion of genealogy. Nevertheless, the question of how to adopt a genealogical approach in the scholarly research on the performing arts and their histories requires further scrutiny, both on the level of methodology and with regard to concrete research outputs.

© Image: Socìetas Raffaello Sanzio / Chiara Guidi, Notes for Voyage au bout de la nuit (1999)